The Middle Ages often conjure images of dirt and squalor, a stark contrast to the sophisticated hygiene of ancient Rome. However, this era’s approach to cleanliness was far more nuanced than popular myths suggest. While many medieval practices might not align with modern standards, people of the time demonstrated a surprisingly practical approach to personal and communal hygiene, shaped by their social status, resources, and deeply religious worldview.

Bathing in the Middle Ages: Between Necessity and Suspicion

Contrary to the common belief that medieval people rarely bathed, historical evidence suggests they understood the importance of cleanliness, albeit in ways shaped by their circumstances and religious beliefs.

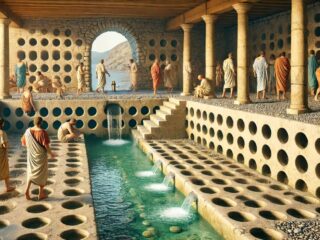

In early medieval times, public bathhouses were relatively common, continuing the Roman tradition. By the 13th century, bathhouses had proliferated across Europe, often serving as social hubs. These establishments, called stews in England, featured large communal baths filled with heated water. They were popular with both men and women, though they sometimes garnered a scandalous reputation due to their association with prostitution.

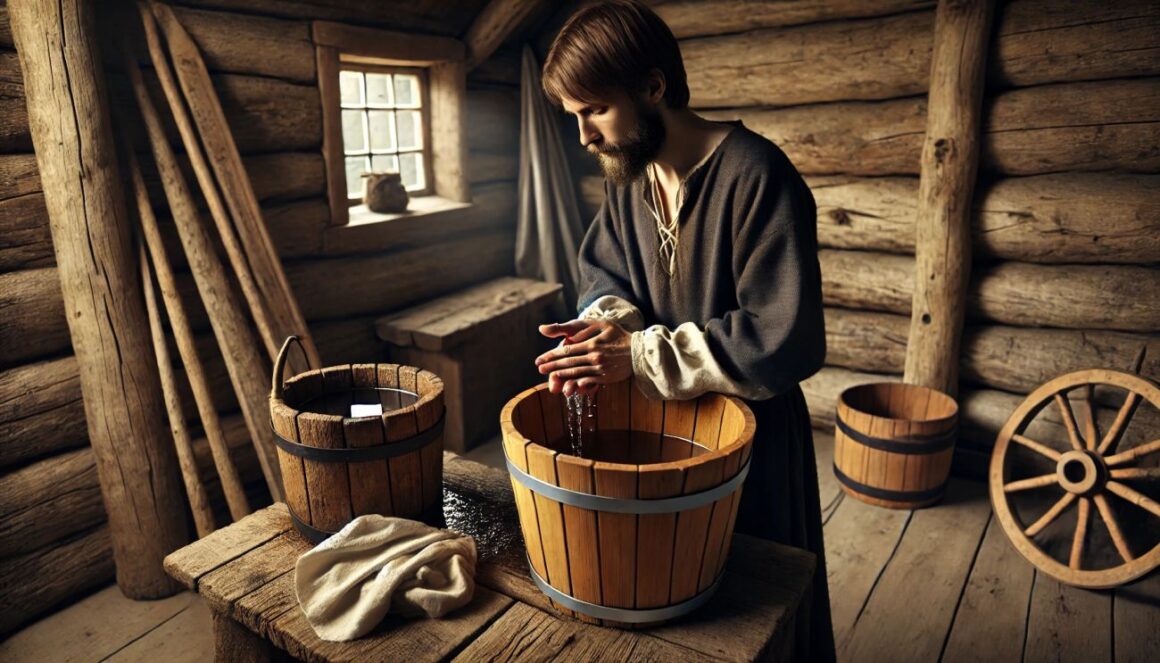

At home, peasants and townsfolk often bathed using a wooden tub filled with water heated over a fire. This practice was more common among wealthier households, as heating water required considerable effort. For the less affluent, washing hands, faces, and feet daily sufficed. Full-body baths were taken less frequently, often reserved for special occasions or when illnesses were believed to require it.

However, by the late Middle Ages, the Black Death and other plagues led to a decline in public bathing. Many feared that open pores, caused by hot water, made the body vulnerable to disease. The Church also began associating public bathhouses with immorality, further diminishing their use.

Oral Hygiene: Natural Solutions for Clean Teeth

Medieval people cared about their teeth and breath, employing various natural remedies to maintain oral hygiene. Chew sticks or small wooden twigs were used to clean teeth, while cloths or fingers rubbed with salt or powdered herbs helped scrub away residue. Charcoal, crushed eggshells, or ground bones mixed with water were used as tooth-cleaning pastes.

Breath fresheners included chewing mint, fennel, or cloves, especially for those who could afford such luxuries. While these methods lacked the efficacy of modern dentistry, they reveal an awareness of oral hygiene that contradicts the stereotype of medieval people neglecting their teeth.

Despite these efforts, tooth decay was common, particularly among the wealthy, whose diets included more sugary foods like honey. Tooth extraction, often performed by barbers or untrained practitioners, was a painful last resort for severe dental problems.

Grooming: Hair, Skin, and Nails

Personal grooming played a significant role in medieval life, though practices varied greatly by class and gender.

Haircare: Men typically wore their hair short and neat, while women kept their hair long, often braided or covered with veils, wimples, or headdresses. Combs made of wood, bone, or ivory were widely used to detangle hair and remove lice, a persistent issue in medieval Europe. Wealthier individuals might use oils or perfumes to condition their hair and scalp.

Beards: Attitudes toward beards varied over time. In some periods, clean-shaven faces were fashionable for men, while in others, beards were seen as symbols of wisdom or piety. Monks, for instance, were often required to shave their faces as part of their religious vows.

Skin Care: Both men and women washed their faces regularly using water mixed with herbs like chamomile or rose. Women, especially of the upper class, used cosmetics to lighten their skin, as pale complexions signified nobility. Ingredients like lead-based powders or crushed pearls were used, though some were toxic.

Nail Care: Clean nails were a mark of civility. Wealthier individuals maintained manicured nails, using knives or special scissors to trim them. For peasants, practicality dictated shorter nails to accommodate labor-intensive tasks.

Menstrual Hygiene: Managing the Unmentionable

Medieval texts rarely mention menstruation, reflecting societal discomfort with the subject. However, women had practical methods for managing their periods. Absorbent materials like wool, linen, or moss were fashioned into pads or tampons, often secured with belts. These materials were washed and reused.

The Church’s teachings influenced perceptions of menstruation, often framing it as a symbol of impurity. Women were sometimes discouraged from entering churches during their periods, though such practices varied widely across regions and communities. Despite these stigmas, menstruation was generally accepted as a natural part of life, and midwives often provided practical advice for managing it.

Toilets and Waste Management: Functional but Far from Glamorous

Sanitation in the Middle Ages ranged from rudimentary to surprisingly sophisticated, depending on location and resources.

Privies and Chamber Pots: In rural areas and poorer households, simple pits or outdoor privies served as toilets. Urban homes relied on chamber pots, which were emptied into cesspits or directly into the streets—a practice that contributed to foul-smelling cities.

Monasteries and Castles: Wealthier establishments like monasteries and castles had more advanced facilities, including latrines connected to flowing water. The famous Garderobe in castles was a narrow chute that deposited waste into a moat or cesspit below.

Efforts to maintain cleanliness in cities included laws regulating waste disposal. In 1388, England passed one of the first sanitary laws, mandating that waste not be dumped in public streets or waterways.

Religion’s Role in Hygiene Practices

Religion heavily influenced hygiene in the Middle Ages. Christian teachings emphasized the purity of the soul over that of the body, sometimes leading to neglect of personal cleanliness. Saints and ascetics, like St. Francis of Assisi, were often celebrated for their rejection of worldly comforts, including bathing.

Yet, the Church also played a positive role in hygiene. Monasteries provided clean water and bathing facilities, often maintaining higher hygiene standards than the general population. Monastic rules, like those of the Benedictines, required regular washing of hands and feet, particularly before communal meals or prayers.

Trivia and Lesser-Known Facts

- Perfumes and Deodorizers: Medieval people used herbs like lavender, rosemary, and thyme to mask unpleasant odors. Sachets of dried flowers, called pomanders, were carried to provide a pleasant scent.

- Lice and Vermin: Combs and herbal remedies were used to combat lice, a constant nuisance. Wealthy individuals sometimes had their clothing boiled or baked to kill pests.

- Bathing Superstitions: By the late Middle Ages, some believed that bathing too often could weaken the body or open it to illness, leading to a decline in regular bathing among certain groups.

- Handwashing Rituals: Washing hands before meals was a widespread custom, often performed with scented water poured from elegant pitchers in wealthier households.

Conclusion

Daily hygiene in the Middle Ages was shaped by a complex interplay of practicality, resources, and religious beliefs. While the era lacked the scientific understanding of germ theory, medieval people were far from indifferent to cleanliness. From bathing rituals to grooming habits, they devised creative solutions to stay clean and presentable in challenging conditions.

Though their practices might seem crude by today’s standards, they reflect a resourcefulness and adaptability that bridged the gap between the ancient and modern worlds. Exploring medieval hygiene reveals not only the realities of the time but also the enduring human desire for cleanliness, comfort, and dignity.